Insights to Understand Markets in 2024

January 18, 2024

How to Be Memorable

March 17, 2024

“Whatever you’ve been told about your retirement, odds are that it’s wrong,” says Allison Schrager, author of An Economist Walks into a Brothel: And Other Unexpected Places to Understand Risk. She attributes this to three widely held myths:

- The most important thing in retirement is to maximize the return on your investments.

- Most people haven’t saved enough and therefore a crisis looms.

- I won’t see Social Security benefits.

I will provide the link to Ms. Schrager’s article below if you’d like to read her defense of why these are myths. The focus of this blog post is the first myth. Among the misconceptions she addresses is that most retirement investing and withdrawal rules are based on institutional investing. And people are not pension funds.

The most important way that households differ from pension funds is their ability to be flexible in response to circumstances. She also highlights that the goal of pension funds is to “keep their pile of money as big as possible,” and while many people have a wish to leave a legacy gift to charity or to beloveds, most people are comfortable spending down their portfolio. The trouble is they don’t know how much they can spend without putting their financial security at risk.

I like to say that I wish we were called Financial Preparers rather than Financial Planners, because there are many uncertainties that can’t be “planned” for: how long will I live; will I get sick and need expensive care and if so for how long; how will my investments perform; will anything happen to the income I’m counting on?

This uncertainty is uncomfortable, and the stakes are high. There are highly consequential decisions to be made with insufficient data and unknowable outcomes.

We like to think we are rational and logical creatures and that the answers can be found in the technical side of our brains: investments, taxes, cash flow. What I see happens is that discomfort activates the amygdala, the flight-fight-freeze part. It contributes to the thinking on the personal side of our brains: emotions, hopes and dreams, self-esteem and sense of well-being. Both sides are equally important and complex, but it is the personal side that drives decision-making.

If your money story—formed early in childhood before you got to kindergarten—helped to shape an attitude toward risk and reward that sounds like, “Life is short, eat dessert first,” you might be more likely to take aggressive risk with your investments and seek the comfort of one-size-fits-all spending rules like the popular 4% rule. You want to provide yourself with a comfortable lifestyle and believe you’ll continue to be able to do so if you make enough money on your investments year in and year out. Because you need to see this steady return in your portfolio, the inevitable rollercoaster of market volatility causes stress. This approach doesn’t provide protection from the downturns or a method to assess their impact on your plan.

On the other end of the spectrum, if your money story helped to shape an attitude toward risk and reward more like, “Use it up, wear it out, make it do or do without,” you are likely holding a lot of CDs or cash, and your comfort and satisfaction about the way you handle money comes from knowing you’re doing all you can to never run out. You more than likely have more money than you will ever need and even so might still feel insecure. This approach misses the opportunity to explore the possibilities available to you, whether it’s “giving with a warm hand not a cold one” to charities that matter to you or family members, or allowing yourself to loosen the purse strings and elevate your lifestyle in ways that bring you joy.

I believe that financial professionals need to help their clients bridge the gap between the two sides of their money brains.

On the technical side, there is good evidence to support that households can adjust their spending dynamically in response to ups and downs in the performance of their portfolio, and this dramatically changes the outcomes from what is projected when you use a fixed rate. Advances in computer power and technology allow us to leverage software to help our clients make better decisions about when to make those adjustments. It’s called the risk-based guardrails model. It gives us a method to quantify the myriad of decisions we’re going to have to make in the future, so we know when and how much to adjust rather than leave it to guesswork or formulas that don’t apply to the individual situation.

On the human side, it’s important to look at what people are taking in from the world around them as well as their money story that informs the emotional base from which they make their decisions. We know that advancements in technology have a peril side, as well as the promise side I’ve just discussed above. Much of our media, especially screaming headlines, clickbait news, and the echo chamber of social media, perpetuate anxiety and alarm.

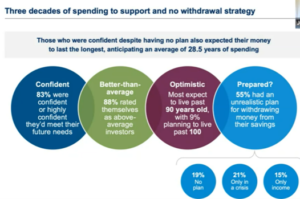

Research from PIMCO suggests that there is a paradox: those who are high in confidence and low in preparedness expect their money to last the longest, meaning that people who have little often feel quite secure. Financial advisers regularly see that people with more money than they will ever need often feel the most insecure. As “Sketch Guy” Carl Richards says, “The conclusion this forces me to draw is that if security exists at all, it is a feeling . . . not a number. The good news is that means we can have some control over it. The bad news is that means it is up to us to learn how.”

Source: PIMCO

http://www.advisorperspectives.com/articles/2023/12/27/three-myths-about-investing-for-retirement